Many songs start as poems, one of the most famous is Harry Chapin’s Cats In The Cradle which was only intended as poem and written by his wife Sandy about their son, but Harry loved it so much he put music to it and made it a classic. Some songwriters, who are not really poets, are given titles like Billy Bragg who is often dubbed the bard of Barking and then there is John Cooper Clarke who famously mixes the two and had been dubbed the bard of Salford.

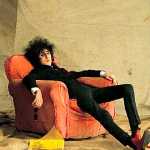

John burst onto the scene in the 1970s as the warm-up act for bands like the Buzzcocks, Joy Division and the Fall, and quickly earned a reputation as a punk poet writing witty urban ballads delivered with a sneer. He altered the course of punk, bringing a more humorous northern vibe to the table. He originated playing gigs with more of a stand-up undertone in his hometown of Salford and soon began writing more biting social commentaries, the renowned Beasley Street being one example.

“To me it’s a very patchy piece, some of it works better than others,” Clarke revealed, “Yet I think it’s the one the people seem to think is a very important piece. The reason why people probably hold Beasley Street in such affection is down to the Beasley Streets that we all know,” he continued. “The fully furnished dustbins that lurk in provincial northern towns or London outskirts. With almost Dickensian colour and flare.” He captures the very essence of the kitchen sink melodrama of Britain’s most poverty stricken areas, whilst raising important questions about their existence and the nature of people’s attitude towards them simply by holding up a mirror. The often divisive production that Martin Hannett brought to John Cooper Clarke’s poetry works to best effect here, complimenting the dark undertones and careful alliteration of ‘in an X certificate exercise ex-servicemen excrete’. It also contains the line ‘Keith Joseph smiles and a baby dies, in a box on Beasley Street’. When it was released, the BBC censored the words Keith Joseph as he was a cabinet minister at the time.

The lines ‘People turn to poison quick as lager turns to piss, sweethearts are physically sick every time they kiss’ speaks volumes of his thoughts and then ‘For a man with a Fu Manchu moustache, Revenge is not enough’ a line which wouldn’t seem out of place in Bob Dylan’s Desolation Row, conjures up vivid images of nastiness.

When asked recently in a rare interview with NME if there was a real Beasley Street, Clarke replied with, “Well inspiration is a divine thing. And the only way to open up to it is to work, like justice is a divinity whilst Law is a human attempt to grasp it. ”

Neighbourhoods are always rich with inspiration. But the most important thing is just not to lose concentration. You can start writing about something you don’t give a shit about and find yourself in the midst of a masterpiece, for instance, I’ve written two numbers about Belgium recently…”

By the early eighties the music had changed and Clarke seemed forgotten. What happened? Clarke tells, “The taint of punk was the kiss of death once the eighties arrived, I mean, how was I going to survive alongside bands like Wham!?” While the British public turned to disco and new romantic, Clarke turned to heroin. In the much publicised tales of his life, the eighties had become his ‘lost decade’, his spiralling addiction crippling his ability to write anything at all. “It didn’t mean I’d lost my desire for work,” he ponders, “Because, if anything, there was even more reason for me to work than ever. I needed the money to go shopping, didn’t I? But it was a feral time, the eighties.” He would have died a forgotten man by that decade’s end. But instead he spent the next 20 years touring again, always – he says – “under the radar”. People started to take notice once again. Earlier this year, BBC4 made a reverential documentary about him which featured the likes of Steve Coogan, Bill Bailey and Stewart Lee waxing lyrical over his contribution to poetry, and reasserting his position as one of the greatest voices of his generation.

In 2003 Alex Turner from the Arctic Monkeys sighed John as a major inspiration, He said, “To the nine-year-old me, he was simply another gruff voice on my post-punk compilation. It wasn’t until I started getting older that I realised the true meaning of the lyrics and the genius that was hidden in and amongst the words. For instance, the lines ‘Sleep is a luxury, they don’t need a sneak-preview of death’ and ‘Keith Joseph smiles and a baby dies’ were taking any naivety remaining in my young mind, dousing it in petrol and setting it ablaze. But the Bard of Salford isn’t merely my continued inspiration, he’s also the root of my very existence; it was at one of his concerts that my parents first met each other. So you can imagine how I started getting all spiritual when synchronicity found JCC himself sitting two seats away from me on the London Euston – Glasgow Central train.”

In a more recent interview with the NME, John was asked what was it like to be on the scene whilst punk was at its peak. His answer: “Shite! Well, in retrospect, it was fantastic. But at the time it seemed shite. I read a figure recently that said at the time there was almost one million unemployed and that, in itself, is something to be cheerful about. Whilst punk was social commentary, it was never really that degrading – y’know – nobody died. It was a good gateway into showbiz for the working class; it laid a path for future artists who didn’t own a three million pound recording studio. It was an impulse to make music cheaply, without compromising on the quality.”

Thirty years on John has updated Beasley Street as Beasley Boulevard, he explained why, “Well, it was kind of natural as thirty years later I was doing a programme for Radio 4 called Bespoken Word and they asked me to do Beasley Street, so I said, it’s been done so much and neighbourhoods don’t stay the same. Why don’t I rewrite it but thirty years on?’ It was a commission really. That’s how it came about.”

In 2012, he was offered and accepted a cameo in Plan B’s debut film Ill Manors, and also guested on the soundtrack. “I was a bit nervous of doing it at first, because I’m not quite au fait with that whole white Jamaican east London patois thing,” he says. “I didn’t want to look like some old twat running to keep up with the kids of today but, at the same time, I didn’t want to look like yesterday’s news, either.”