Germany gave us some wonderful musicians, classical composers like Beethoven, Bach, Brahams, Wagner, Strauss, Schumann, Handel and Mendelssohn, contemporary tunesmiths like Kurt Weill, Holger Czukay, Harold Faltermeyer, James Last and Helmut Zacharias and then wordsmith Maestro’s like Gerald Hoffnung and Bertolt Brecht, all who made their mark. This week’s subject features words by Brecht whose most famous piece has got to be Mack the Knife from The Threepenny Opera, but this time it’s the less obvious Baal, his first full length play which he wrote in 1918. It had been on the stage many times and adapted by David Bowie for television in 1982.

Not only was it Brecht’s first full length play it was also his earlier and written as a response, in a parody style, to the German playwright and Nazi poet laureate Hanns Johst’s 1917 play Der Einsame which translates as The Lonely. Baal was created as a monster of sensuality and self-gratification with a repulsive appearance who thought he was irresistible to women and all men would be jealous of him. The story describes how he seduces any female that he encountered and then left them often pregnant and sometimes contemplating suicide. He then murders his best friend, goes on the run and dies alone in a woodcutter’s cottage.

Brecht, as described by Bowiesongs, was inspired by performers he had seen in his native Bavaria, like Karl Valentin, a clown who was Germany’s answer to Charlie Chaplin, and Joachim Ringelnatz, a sailor/minesweeper turned poet and cabaret performer. Brecht’s poems were often written to be chanted or sung.

The 1970 TV movie of Baal, which was all in German, was directed by Volker Schlöndorff and starred Rainer Werner Fassbinder in the lead role. In January 1981, the director Alan Clarke, who had recently directed the brilliant, but violent prison drama Scum had the idea to revive Baal for the BBC. He worked with the producer Louis Marks and Clarke had the idea to use split-screen to convey the Brechtian dramatic technique of characters addressing the audience during the play. The role of Baal required a charismatic performer who could act and sing and was prepared to play a vile looking character. Clarke’s initial preference for the role was Steven Berkoff, but was ruled out because he thought Berkoff would want to present it in its original form. Clarke then remembered seeing David Bowie in The Elephant Man and remembering Bowie’s ability to create characters suited the role perfectly. He also believed Bowie had an interest in Weimar Germany, so he went to see him in Switzerland to offer him the role. As it was for the BBC, Bowie had no choice, if he wanted the role, to accept the standard BBC fee of £1,000.

Clarke was one of the most talented directors at the time and had done a lot of work for the BBC, but relationships had become a bit strained after the Corporation refused to screen Clarke’s Scum citing that it was too violent and also how it ostensibly portrayed the failings of the borstal system so, in turn, Clarke’s work for television became more radical. In 1978, as part of BBC 1’s Play of the Month series, Clarke had produced the play Danton’s Death as written by Georg Buchner which presents a harsh view of human existence as being a struggle to preserve the life force and Baal was perceived to compliment it with its bleak and punishing story.

The BBC’s values came into question, as they often are, because the film was billed as ‘David Bowie in Baal‘ thus promoting a star over a production, but obviously the reason being is that it was likely to attract a bigger audience. John Willett, who had translated the script into English, was amazed to learn during rehearsals that Bowie knew as much about the Weimar region of Germany and about Brecht as he did. Bowie was endlessly reading about it during his time in Berlin in the mid-late seventies when he shared an apartment with Iggy Pop.

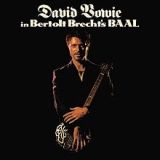

Bowie had come to loathe RCA records with whom he’d been signed since 1972. He was due to record one more album for the label, but instead recorded five tracks for Baal which eventually were released on an EP as a parting ‘gift’ to the label. The lead track was Baal’s Hymn with the other four being Remembering Marie A, Ballad of the Adventurers, The Drowned Girl and The Dirty Song which were translated by Ralph Manheim and John Willett with the exception of The Drowned Girl which Kurt Weill had done.

Check out the label and you’ll notice the co-writing credit Dominic Muldowney. Dominic in a classical composer and I was interested in knowing his input, so I met him in London for an exclusive and fascinating interview. He told me how he first got involved, “Interestingly, the person who translated Brecht was John Willett who was a very good friend of mine, we both lived in France at the time and he was a maverick, a brilliant translator and he said to me one day, ‘don’t you think David Bowie would be perfect as Baal? I think I’m going to write to the BBC and suggest it’ and when you mention the name Bowie then of course they are going to leap on board.”

Dominic had no knowledge of what was to come with David Bowie but, coincidentally, Dominic had begun reading and researching Brecht a good two months before he got involved with Bowie, he explained, “At the back of a book of poetry by Brecht, he wrote some little melodies that I sourced and they were melodies that he would have played on the guitar or sang when he first did the play back in about 1920 and it’s very interesting because some of these tunes became very famous 10 years later in the Mahagonny Suite. What was strange is that they don’t look like music, they were more like little bits of plainsong and they are just one line, just a fragment of melody. Two months later David rang me up and said he had a very interesting idea for me and would I like to really beef the those little tunes up into orchestral songs because he thought it would be a great way for him to extract himself from the RCA deal which required him to do one more album, so I agreed and my job really was to extend and develop them and these little fragments became the beginning of the thing that David accompanied himself with on the banjo. In just two and a half weeks I re-thought everything and scored them for much bigger orchestrations. David said to me that he would book a studio and I thought he meant in London but it turned out to be a studio he was very fond of in Berlin called Hansa which was known as Hansa by the Wall because when you looked out of the studio you could see the soldiers walking up and down, you really were that close to the Wall.”

So Dominic flew to West Berlin (as it was then) and explained to me about the musicians, “I don’t know who fixed the orchestra but the accordion player, who featured very prominently, was quite an old guy and I asked him if he remembered the old days like the thirties and he said, ‘oh yeah I was in the first performance of The Threepenny Opera, so obviously whoever arranged it had been told that Bowie was coming and he wanted a real proper German Kurt Weill sound, so they just rounded up all the old guys. There were 12 of them although the producer, Tony Visconti, made it sound like 50 because he could get a string quartet and make it sound like power chords on a guitar. There’s a bit in Baal’s Hymn just before the voice comes in which is very quiet but Tony squashed the sound right up so it had a big thump to it. I was watching a man way ahead of his time on the desk.”

The night before recording David took Dominic for a night out, “I remember David saying, ‘come on, we’re going clubbing,'” Dominic explained, “I was more worried about getting back to have a good night’s sleep, but anyway we went out, went to three different clubs and still managed to catch some sleep. I got to the studio, a bit hung over, at 10 o’clock and David wasn’t there and I said to Tony, ‘what are we going to do?’ and he said, ‘just record’, but that’s not so easy, it’s not all 1,2,3,4, so what I had to do was try to remember his performance and I had a tiny mic right by my mouth and I’m whispering what I could remember. Tony said that would be fine and David can use that as a guide track. Anyway we got everything done in the morning, all the musicians left at two o’clock after just four hours and Tony just kept saying, ‘don’t worry, I can just drop his voice in.’ David turned up at four o’clock looking immaculate with the scarf and the hat just like Frank Sinatra looked on his album covers, and what astonished me the most was that I learned that David recorded everything back to front, so in this case he recorded the ninth verse first and then the eight and then the seventh etc and he did that for everything. I have no idea why. But two hours before David arrived Tony was already mixing it.”

Bowie knew the tracks would be hard for radio to programme and was even heard to have said at the time, “you thought Low was too uncommercial, good luck selling this one.” But Bowie, was on the cusp of migrating from cult status to mainstream acceptance, had enough followers who bought the track which propelled it to number 29. In 1983 he signed to EMI America and his career was upped a notched when he released Let’s Dance, the title track from the album, both of which topped the UK charts. The next two singles, China Girl and Modern Love both made number two giving Bowie three consecutive top two hits for the first time.

It was his association with Bowie that got Dominic his next project the following year and he told me how he got that gig, “Interestingly, and I only found this out a few years ago, when I read a book about a film called Betrayal which was the first feature film I ever did and was Harold Pinter’s portrayal which starred Ben Kingsley and Jeremy Irons, and this guy rang me up one day and said, ‘Hi, it’s Sam Spiegel here and I’m ringing from Harold Pinter’s office’ and I asked if it was a wind up, and he said, ‘no, hang on, I’ll put you on to Harold, he said he knows you’, and then Harold came on the phone and said, ‘Hello Dominic old chum how are you? ‘and it turns out that David (Bowie) had been asked to write music for Betrayal and I think he felt that what he was doing couldn’t do anything to help the film and he happened to say to Sam Spiegel, in front of Harold Pinter, ‘I’ve just been working with a classical composer and you want to ask him, he’s brilliant and his name is Dominic Muldowney and before Sam could say ‘never heard of him’ Harold yelled, ‘Dominic? Wow, he’s a friend of mine and he’s got to do it. And that is how I got my first feature film.”

Tony Visconti, in a piece on his Facebook page last year, said, “I felt Baal was a bit over-looked, this neglected work of art was the last thing David and I recorded at Hansa Studios (by the Wall) in Berlin. The unmistakable three microphone technique is very obvious, especially when David sang very loud. You can hear that signature ‘Heroes’ sound in the room reverb. There was some slight plate reverb on the vocal but I used the room reverb extensively on David’s vocals and the small ‘pit’ orchestra (one of each instrument, clarinet, trumpet, accordion, double bass, violin, etc.) Dominic Muldowney, our orchestrator, is an authority on Brecht and wrote these very precious and authentic arrangements to widen the scope of the songs composed by Brecht. David was meant to sing live with the orchestra at Hansa, but he arrived too late to the studio, only in time for the last piece to be laid down. This was obviously before mobile phones so we were worried about his whereabouts. He overslept. These recordings were financed by David, not by the label. He played the incorrigible Baal in the BBC musical but he was only accompanied by no more than a few instruments. He wanted to realise the full potential of the music by recording them properly. He was strapped for cash in those days, involved in two lawsuits with former managers, so this was a labour of love for him. As you can hear, his vocals are sterling. I can’t remember if we mixed all the songs that evening or came back the next day, but it didn’t take long, I mixed them all in the same session. The only video David made of one of these songs is The Drowned Girl, directed by David Mallet in my Good Earth studios in Dean St, Soho. The ‘acting’ musicians in the video are none other than Coco Schwab on saxophone, myself on classical guitar, Mel Gaynor on trumpet and Andy Hamilton on clarinet. We also filmed Wild Is the Wind during the same session (such were the extremely low video budgets back in those days). I’m so happy this music has come back into my life. About two years ago I brought it up in a conversation with David and he was adamant that it was not available any longer on any format and I took his word for granted. I must say it hasn’t aged one bit. It is a timeless recording and a feather in David’s cap. He always loved musical theatre and he did Bertolt Brecht proud with this one.